This is our backup site. Click here to visit our main site at MellenPress.com

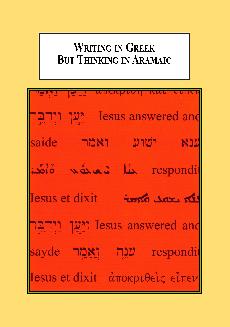

Writing in Greek But Thinking in Aramaic: A Study of Vestigial Verbal Communication in the Gospels

| Author: | Reiter, C. Leslie | |

| Year: | 2012 | |

| Pages: | 204 | |

| ISBN: | 0-7734-4062-3 978-0-7734-4062-3 | |

| Price: | $179.95 | |

In this monograph the author investigates the syntactic construction found in the Semitic languages known as verbal coordination as it relates to the translation and therefore the interpretation of the scriptures. In the course of his analysis, the author also discusses grammaticalization that has occurred to translate the function of the word from Hebrew to Greek. According to the author, translations of this construction account for certain awkward expressions in the Greek Gospel texts, particularly Mark and John, because the writers were thinking in Semitic and writing in Greek. There are significant implications for Bible scholars, translators and linguists.

Reviews

“Reiter’s study makes significant contributions to several areas of biblical scholarship. First, by demonstrating the existence of verbal coordination in ancient Hebrew and Aramaic, he provides a corrective to the tendency to emphasize lexical over syntactical categories in the development of scholarship of ancient Semitic languages. Second, by showing that a unique feature of Semitic syntax has influenced the style of New Testament Greek, Reiter reinforces the level to which a Semitic worldview pervades the New Testament, an understanding that has been growing in recent years. And, finally, in the demonstrating the existence of a previously unrecognized syntactical nuance in the Gospels, Reiter’s study should make real contributions to future translations and interpretations of the Gospel material.”

-Dr. Robert F. Shedinger,

Luther College

“This book applies a beautifully simple idea to a text of fundamental importance. The simple idea is that, if a writer is thinking in one language while writing in another, what is written will contain traces of what is thought. The fundamental text is the New Testament. Although the Gospel writers were writing in Greek, they were thinking in Aramaic--the implications of this study for how we understand certain sentences in the New Testament are potentially far reaching and certainly worth consideration. It is certain that readers will not agree with all the conclusions, but it is equally certain that all readers will benefit from and be struck by some, if not most, of them.”

-Dr. Siam Bhayro,

University of Exeter

“Two strengths set this apart from previous work within the field of the Aramaic background of the New Testament. First and foremost, the consideration is grammatical in the proper sense, so that the reader is exposed to issues of comparative syntax and construction within the task of translation. That focuses is especially pertinent to the philology of ancient texts, where it is all too often lacking.”

Dr. Bernard Iddings Bell,

Bard College

-Dr. Robert F. Shedinger,

Luther College

“This book applies a beautifully simple idea to a text of fundamental importance. The simple idea is that, if a writer is thinking in one language while writing in another, what is written will contain traces of what is thought. The fundamental text is the New Testament. Although the Gospel writers were writing in Greek, they were thinking in Aramaic--the implications of this study for how we understand certain sentences in the New Testament are potentially far reaching and certainly worth consideration. It is certain that readers will not agree with all the conclusions, but it is equally certain that all readers will benefit from and be struck by some, if not most, of them.”

-Dr. Siam Bhayro,

University of Exeter

“Two strengths set this apart from previous work within the field of the Aramaic background of the New Testament. First and foremost, the consideration is grammatical in the proper sense, so that the reader is exposed to issues of comparative syntax and construction within the task of translation. That focuses is especially pertinent to the philology of ancient texts, where it is all too often lacking.”

Dr. Bernard Iddings Bell,

Bard College

Table of Contents

Forward by Bernard Iddings Bell

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

Chapter I Introduction

1.1 Answered and Said

1.2 Preliminary Observations

1.2.1 Verbal Coordination

1.2.2 Grammaticalization: Changes in Grammar

Chapter II The Grammatical Structure of Verbal Coordination

2.1 Scholarly Notice of Verbal Coordination in Hebrew

2.2 Scholarly Notice of Verbal Coordination in Aramaic

2.3 Scholarly Notice of Semitisms in the Greek New Testament

2.4 Scholarly Notice of Verbal Coordination in the Commentaries

2.5 Grammaticalization and Verbal Coordination

2.5.1 Definitions and Concepts of Grammaticalization

2.5.2 Semitic Grammaticalization

2.5.3 Verbal Coordination as an Example of Grammaticalization

Chapter III Verbal Coordination in Late B.C.E.--Early C.E. Texts

3.1 Translations of Citations from Appendix A and B

3.1.1 The Septuagint and Vulgate

3.1.2 TheTargumim

3.1.2.1 Targum Onqelos

3.1.2.2 Targum Nebi’im (Targum Jonathan)

3.1.3 Aramaic Translations from Qumran

3.1.4 The Old Syriac Gospels

3.1.5 The Peshitta

3.2 Documents Other Than Translations of the Hebrew Bible

3.2.1 Additions to the Hebrew Bible Found in the Targumim

3.2.1.1 Targum Onquos

3.2.1.2 Targum Nebi’im (Targum Jonathan)

3.2.2 Aramaic Documents from Qumran

Chapter IV Vestigial Verbal Coordination

4.1 Indicative Mood

4.1.1 Verbs of Speaking

4.1.1.1 Two verbs of utterance used in coordination

4.1.1.2 Verbs of action coordinated with verbs of speech

4.1.2 Verbs of Motion

4.1.2.1 Verbs meaning come or go coordinated with another verb

4.1.2.2 Verbs meaning rising coordinated with verbs of action

4.1.2.3 Other verbs of motion in coordination

4.1.3 Other Types of Verbs in Coordination

4.1.3.1 Verbs of seeing coordinated with verbs of action

4.1.3.2 Other verbs of action coordinated

4.2 Imperative Mood

4.2.1 Syndetic Construction

4.2.2 Asyndetic Construction

4.3 Participle Plus Verb

Chapter V Concluding Remarks

5.1 Summary and Recapitulation

5.1.1 Significance of Aramaic

5.1.2 Verbal Coordination

5.1.3 Gramaticalization and Verbal Coordination

5.2 Implications for Biblical Studies

5.2.1 Verbal Coordination and Translating

5.2.2 Theological Implications of Verbal Coordination 5.3 Implications for the Life and Teachings of Jesus

5.4 Possible Objections to This Investigation

Appendices

A. Answered and Said in KJV of Bible

B. Verbal Coordination in the Hebrew Bible

C. Comparison of Syriac Versions with the Hebrew and Greek Text for the Words Answered and Said in the KJV

D. Indicative Vestigial Verbal Coodination in the Gospels

E. Participial Vestigial Verbal Coodination in the Gospels

F. Imperative Vestigial Verbal Coodination in the Gospels

Bibliography

Indices

Modern Authors

Persons

Subjects

Versions and Editions Scriptures Ancient Manuscripts and Codices Greek Words Hebrew and Aramaic Words Transliterated Terms

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

Chapter I Introduction

1.1 Answered and Said

1.2 Preliminary Observations

1.2.1 Verbal Coordination

1.2.2 Grammaticalization: Changes in Grammar

Chapter II The Grammatical Structure of Verbal Coordination

2.1 Scholarly Notice of Verbal Coordination in Hebrew

2.2 Scholarly Notice of Verbal Coordination in Aramaic

2.3 Scholarly Notice of Semitisms in the Greek New Testament

2.4 Scholarly Notice of Verbal Coordination in the Commentaries

2.5 Grammaticalization and Verbal Coordination

2.5.1 Definitions and Concepts of Grammaticalization

2.5.2 Semitic Grammaticalization

2.5.3 Verbal Coordination as an Example of Grammaticalization

Chapter III Verbal Coordination in Late B.C.E.--Early C.E. Texts

3.1 Translations of Citations from Appendix A and B

3.1.1 The Septuagint and Vulgate

3.1.2 TheTargumim

3.1.2.1 Targum Onqelos

3.1.2.2 Targum Nebi’im (Targum Jonathan)

3.1.3 Aramaic Translations from Qumran

3.1.4 The Old Syriac Gospels

3.1.5 The Peshitta

3.2 Documents Other Than Translations of the Hebrew Bible

3.2.1 Additions to the Hebrew Bible Found in the Targumim

3.2.1.1 Targum Onquos

3.2.1.2 Targum Nebi’im (Targum Jonathan)

3.2.2 Aramaic Documents from Qumran

Chapter IV Vestigial Verbal Coordination

4.1 Indicative Mood

4.1.1 Verbs of Speaking

4.1.1.1 Two verbs of utterance used in coordination

4.1.1.2 Verbs of action coordinated with verbs of speech

4.1.2 Verbs of Motion

4.1.2.1 Verbs meaning come or go coordinated with another verb

4.1.2.2 Verbs meaning rising coordinated with verbs of action

4.1.2.3 Other verbs of motion in coordination

4.1.3 Other Types of Verbs in Coordination

4.1.3.1 Verbs of seeing coordinated with verbs of action

4.1.3.2 Other verbs of action coordinated

4.2 Imperative Mood

4.2.1 Syndetic Construction

4.2.2 Asyndetic Construction

4.3 Participle Plus Verb

Chapter V Concluding Remarks

5.1 Summary and Recapitulation

5.1.1 Significance of Aramaic

5.1.2 Verbal Coordination

5.1.3 Gramaticalization and Verbal Coordination

5.2 Implications for Biblical Studies

5.2.1 Verbal Coordination and Translating

5.2.2 Theological Implications of Verbal Coordination 5.3 Implications for the Life and Teachings of Jesus

5.4 Possible Objections to This Investigation

Appendices

A. Answered and Said in KJV of Bible

B. Verbal Coordination in the Hebrew Bible

C. Comparison of Syriac Versions with the Hebrew and Greek Text for the Words Answered and Said in the KJV

D. Indicative Vestigial Verbal Coodination in the Gospels

E. Participial Vestigial Verbal Coodination in the Gospels

F. Imperative Vestigial Verbal Coodination in the Gospels

Bibliography

Indices

Modern Authors

Persons

Subjects

Versions and Editions Scriptures Ancient Manuscripts and Codices Greek Words Hebrew and Aramaic Words Transliterated Terms